Was it Love or Witchcraft? The Magical Practices of Chinese Empress Chen Jiao

Usually, the Empress of the Han Dynasty was invincible, untouchable, and protected by the law more than anyone else. However, in the case of Empress Chen of Wu, the accusation of practicing black magic destroyed her life. Nowadays, she is remembered as an ancient Chinese witch.

She was the wife of Emperor Wu of Han, who ruled between 141 and 87 BC. Their marriage was arranged and was not based on love. She was her husband’s servant when she was a little girl. Instead of playing and having fun like most children, she had to follow the strict rules laid out for Han Dynasty women.

Traditional portrait of Emperor Wu of Han from an ancient Chinese book. (Public Domain)

Tragedy for the Empress

Most of the facts related to her life come from Chinese literature, which presents them without many precious details for modern researchers or history article wanderlusts looking for thrilling stories.

- Celadon: Appreciating Pottery for its Aesthetic Value and Magical Qualities

- Shui-mu Niang-niang: The Old Mother of the Waters Who Submerged an Ancient City

Chen Jiao had only a few aims in her life: apart from being a good servant and following the rules of the court, she had to deliver children - mostly boys to be precise. Sadly, she had a big problem with getting pregnant and she couldn't deliver the necessary baby. Due to this fact, she stepped into a forbidden side of life –witchcraft. It is unknown if she practiced witchcraft before this problem arose, but it seems that magic was the last place women generally searched for help in such situations.

When the Emperor lost his hope that she would bear him a child, she found a new idea. Although he was still regularly visiting her palace, his anger was growing. The situation became extremely hectic and she started to search for help among the wise women who traditionally aided in these difficult situations around the world.

This was a time when the Emperor had already become more interested in other concubines and the fact cut Chen Jiao’s heart like a knife. To avoid losing the Emperor’s interest she decided to make a desperate step into a realm that could have been very beneficial to her, but was also extremely dangerous. She hoped to use the occult to fix her problems – despite the Han laws. The rules of the time declared the use of magic as a capital offense. It was especially unforgivable amongst the nobility, including the royal family. However, she reached a woman named Chu Fu, who was later a witness in the Empress’ trial.

An Illustration of a witch. (Public Domain)

When the court realized that the Empress practiced magic her life became terribly difficult. Chu Fu confessed that Chen Jiao practiced love magic preparing potions, nailing voodoo dolls of the Emperor and herself depicting sexual acts, etc. When the Empress was accused, her execution was expected, but fate brought her something different. Chu Fu was executed with about 300 other people that were involved in the Empress’ magical practices. Chen Jiao, on the other hand, was deposed from her position in 130 BC and exiled from the capital city. She spent the rest of her life under house arrest at the Long Gate Palace, where she died 20 years later as a lonely woman.

Mystery of Magic Mirrors

It is unknown what kind of other magical practices she used. Many traditional Chinese cultural elements are now forbidden but still practiced quietly within households. Even though it was frowned upon or dangerous, magic didn't disappear in China or other areas around the world. Despite its relative popularity, the situation in China is special because it seems to be more related to the dark side of witchcraft.

Witches by Hans Baldung. Woodcut, 1508. (Public Domain)

Black magic was well known in Ancient China, but research related to this topic is still full of gaps. It is known, however, that one of the most famous methods for practicing magic was ''magic mirrors''. As M. V. Berry explained:

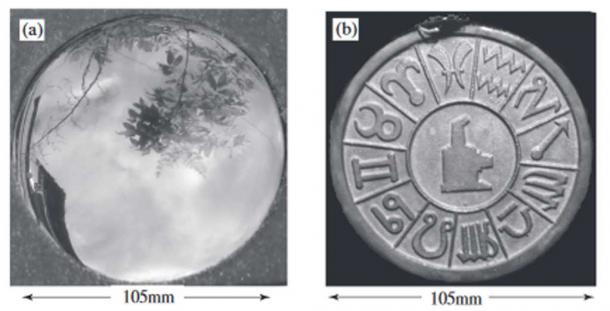

''Cast and polished bronze mirrors, made in China and Japan for several thousand years, exhibit a curious property, long regarded as magical. A pattern embossed on the back is visible in the patch of light projected onto a screen from the reflecting face, when this is illuminated by a small source, even though no trace of the pattern can be discerned by direct visual inspection of the reflecting face. The pattern on the screen is not the result of the focusing responsible for conventional image formation, because its sharpness is independent of distance, and also because the magic mirrors are slightly convex. It was established long ago that the effect results from the deviation of rays by weak undulations on the reflecting surface, introduced during the manufacturing process and too weak to see directly, that reproduce the much stronger relief embossed on the back. Such ‘Makyoh imaging’ (from the Japanese for ‘wonder mirror’) has been applied to detect small asperities on nominally flat semiconductor surfaces.''

(a) Convex reflecting face of magic mirror. (b) Pattern embossed on back face of magic mirror. (M V Berry)

These mysterious artifacts are some of the fascinating magical pieces from Asia. However, the practice of using a “magic mirror” seems to have a strong basis in an unexpected discipline – mathematics. Researchers have to use very sophisticated mathematics to create calculations that explain what happened during the process described above.

- From Magic to Science: The Intriguing Ritual and Powerful Work of Alchemy

- Mystical Science of Alchemy Arose Independently in Ancient Egypt, China, India

Victim of Gossip or a Real Ancient Witch?

Legends say Empress Chen of Wu was a powerful Chinese witch. People who practice witchcraft in China today still consider her their ancestor. Her deposition for committing witchcraft remains the last episode of a series of unexplained events in her life. Did she put a charm on the Emperor to save her life? Or were his mercy and heart so huge that he decided to not sentence her to death? This part of the story will never be known for certain. But the fame of Empress Chen Jiao as a witch remains unquestionable.

Eastern Han Dynasty sculpture of a woman with a mirror. (Public Domain)

Top image: Actress Shen Miao as Empress Chen Jiao from the drama ‘The Virtuous Queen of Han.’ Source: cfensi

References:

Bennet Peterson, Barbara, Notable Women of China: Shang Dynasty to the Early Twentieth Century, 2000.

Creation of Lesser Gods: The World of Daoist Magic, available at:

www.demystifyingconfucianism.info/the-creation-of-lesser-gods

Recent advances in understanding the mystery of Ancient Chinese ''magic mirrors'', available at:

www.eastm.org/index.php/journal/article/viewFile/497/428

Oriental magic mirrors and the Laplacian image by M. V. Berry, available at:

https://michaelberryphysics.files.wordpress.com/2013/07/berry383.pdf